Question

What are some of the chest scores we use to evaluate the likelihood a patient with chest pain is having ACS?

What are some of the chest scores we use to evaluate the likelihood a patient with chest pain is having ACS?

What are the 5 main life-threatening causes of chest pain?

The 5 main life-threatening causes of chest pain you should ALWAYS think of are:

There are a few others that should also cross your mind:

References

Question

What are 3 pretest probability scoring systems used to evaluate patients with a suspected pulmonary thromboembolism?

Answer

There are 3 validated pretest probability scoring systems that can be used to help clinicians decide who can be sent home, who needs a D-dimer, and who goes straight to CT for suspected PTE.

Developed – 1998

Revised – 2000

Simplified – 2001

Developed – 2001

Revised – 2006

Simplified – 2008

Developed – 2008

This score is used AFTER the patient is determined to be low-risk using the Well’s or Geneva score. In patients who are low-risk and PERC negative, there is only a 1.6% false-negative rate for missed PTE. Any one of these would deem the patient PERC positive.

Although it does help us in deciding who maybe at higher risk of PTE, I personally feel these scoring systems help us document who DOES NOT need work-up. There are quite a few patients who come in with non-specific chest pain or shortness of breath, and you should ALWAYS entertain the idea of PTE in these patients. But, not every single one of these patients need a d-dimer or CTA. Better yet, some of these patients can be discharged home without any investigation if they are low-risk and PERC negative.

Below is an algorithm I modified from Jeff Kline using these clinical decision instruments.

All these images are slides from my talk at the 2015 AAPA Conference

References

This is actually a special episode for the PAINE Podcast as I have the opportunity to do a joint-interview podcast with Chip Lange from TOTAL EM. This was the first time I got to dabble with a conversational-style podcast and I think it went pretty good. Chip and I had a great time doing it and will most definitely be doing more of these in the future.

One of the many saying my Army Airborne Ranger dad has instilled in me growing (and one that I still use today) is the seven “P” approach to accomplishing tasks:

What is nice about this saying is that it applies very nicely to the steps of intubation as well.

You need to to have everything at the bedside you MIGHT need prior to any intubation attempt. This includes equipment, medications, and any personnel or team members who will assist. If you even suspect this could be a difficult airway, you should have your plan B and plan C options in the room to ward off the evil spirits.

This also gives you the opportunity to talk with you team about the plan for intubation (how many attempts, progression should plan A, steps of what will happen during the intubation and everyone’s roles during the procedure, etc..), as well as reviewing assisting maneuvers (external laryngeal manipulation, etc.).

In order to decrease any deoxygenation-related issues during the intubation attempt, your patient should recieve 100% oxygen at 15 liters per minute through a non-rebreather mask for 3-5 minutes. This will properly de-nitrogenate and super-saturate all the hemoglobin and give you the time you need to visualize and intubate.

“EAR HOLE TO CHEST HOLE”

For ideal visualization, you want to position your patient so that their external auditory meatus lined up to the sternal notch

There are several different medications you can give for premedication purposes to modify the physiologic response during intubation (lidocaine, opiates, atropine, defasculating agents, etc..), but the main one is the sedative. It is generally poor form to paralyze someone before you sedate them. There are several medications you can choose from for sedation in intubation:

There are 2 choices for classes of paralytics:

Once you patient is properly sedative and paralyze, you can proceed to laryngoscopy.

Capnography

This is used for confirmation of correct placement of the endotracheal in the trachea and tests for end-tidal CO2. There are 2 main types:

Securing the Tube

Once you know you are in the right spot and have been confirmed by capnography, you need to secure the tube. There are different ways to achieve and I often defer to the respiratory therapist or nurse on how they want it secured. There are commercial devices that lock the tube in place and secure using velcro straps, all the way to the old standby of adhesive tape. This is a great site that shows several different ways you can secure the endotracheal tube (http://aam.ucsf.edu/article/securing-endotracheal-tube).

Radiography

Chest xray is the gold standard for the radiographical confirmation of endotracheal placement, as well as ensuring the proper depth. The ideal position for the tube depth should be 3-5cm from the carina or at T3-4 position.

Josh Farkas (PulmCrit) did a great review on endotracheal tube positioning and depth just last week.

Ultrasound is being used more frequently as a confirmatory tool for endotracheal tube placement.

Great review by EmDocs on ultrasound for endotracheal tube confirmation.

Sedation/Analgesia

Now that the tube is in place, secured, and confirmed, you are done right? WRONG!!! Your patient now has a tube shoved into the tracheal and it is a tad uncomfortable. Postintubation sedation/analgesia is PARAMOUNT for good patient care.

You should be shooting for a Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) of -1 to -3 for adequate sedation following intubation.

References

Dyspnea is one of the more common complaints that will bring a patient to the ED for evaluation. The most recent data from the CDC shows more than 3.7 million visits to the ED in the United States for shortness of breath alone and more than 11 million for dyspnea-related complaints (cough, chest pain, etc.).

There are 3 global processes that have to function in series to prevent a patient from becoming short of breath:

5 Main Causes of Hypoxemia

Vitals

History

Physical Exam

Rapid examination should be performed (often while getting the history) to evaluate for impending respiratory collapse:

Any of the above findings should raise your threshold to intubate.

Once these have been evaluated and ruled-out, you can begin a focused physical exam to address the causes of acute dyspnea:

Three main primary goals for the emergent management of acute dyspnea:

References

57-year-old male, with controlled hypertension, presents to emergency department with a 2-hour history of a central, dull, chest pain that does not radiate. He rates it as a 4/10 in severity and denies any aggravating or alleviating factors. He reports some mild nausea and what he reports as “reflux” during this event as well. He denies shortness of breath, vomiting, arm radiation, back radiation, abdominal pain, dizziness, or syncope. His father has HTN, HLP, and had a non-fatal AMI at 62-years-old. He is a never smoker. His BMI is 27.3.

Vital signs show BP-122/82, HR-93, RR-16, O2-100% on room air, and temp-98.0.

Physical exam reveals:

HEENT – NC/AT

Skin – no diaphoresis

Cardiovascular – RRR without M/G/R

Pulmonary – CTA without adventitial breath sounds

Abdomen – S/ND, mild epigastric tenderness to deep palpation

Peripheral Vascular – 2+ pulses throughout

Neuro – A&Ox3, 5/5 strength throughout

EKG is below:

Laboratory Screening:

High-sensitivity troponin (hs-cTnI) – 0.02 ng/dL

CK-MB – 39 U/L

Total CK – 264 U/L

Myoglobin – 22 ng/mL

Answer:

Discharge home with cardiovascular provocative testing as outpatient.

Why? Low risk HEART score. What is the HEART score? Glad you asked.

The HEART score was first published in 2008 to evaluate occurrence of Major Adverse Cardiac Event (MACE) at 6 weeks. MACE defined in the study was any occurrence of AMI, PCI, CABG, or death. The 5 variables they used are:

The HEART score performed better than TIMI and GRACE predicting MACE in acute chest pain patients presenting to the ED.

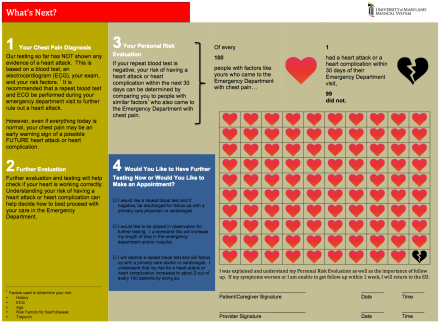

For our patient, he has a HEART score of 3 (age + history + risk factors). We could have a discussion with him regarding the risk of him having a MACE in the next 6 weeks and the risks/benefits of admission and testing now. Below is a nice patient sheet that the University of Maryland (FEAR THE TURTLE) has developed to help with shared decision making in the ED.

University of Maryland. http://tinyurl.com/nc2k65n

References

57-year-old male, with controlled hypertension, presents to emergency department with a 2-hour history of a central, dull, chest pain that does not radiate. He rates it as a 4/10 in severity and denies any aggravating or alleviating factors. He reports some mild nausea and what he reports as “reflux” during this event as well. He denies shortness of breath, vomiting, arm radiation, back radiation, abdominal pain, dizziness, or syncope. His father has HTN, HLP, and had a non-fatal AMI at 62-years-old. He is a never smoker. His BMI is 27.3.

Vital signs show BP-122/82, HR-93, RR-16, O2-100% on room air, and temp-98.0.

Physical exam reveals:

HEENT – NC/AT

Skin – no diaphoresis

Cardiovascular – RRR without M/G/R

Pulmonary – CTA without adventitial breath sounds

Abdomen – S/ND, mild epigastric tenderness to deep palpation

Peripheral Vascular – 2+ pulses throughout

Neuro – A&Ox3, 5/5 strength throughout

EKG is below:

Laboratory Screening:

High-sensitivity troponin (hs-cTnI) – 0.02 ng/dL

CK-MB – 39 U/L

Total CK – 264 U/L

Myoglobin – 22 ng/mL