Rinne Test

Other Known Aliases – none

Definition – bedside test to evaluate hearing loss using a 512hz tuning fork

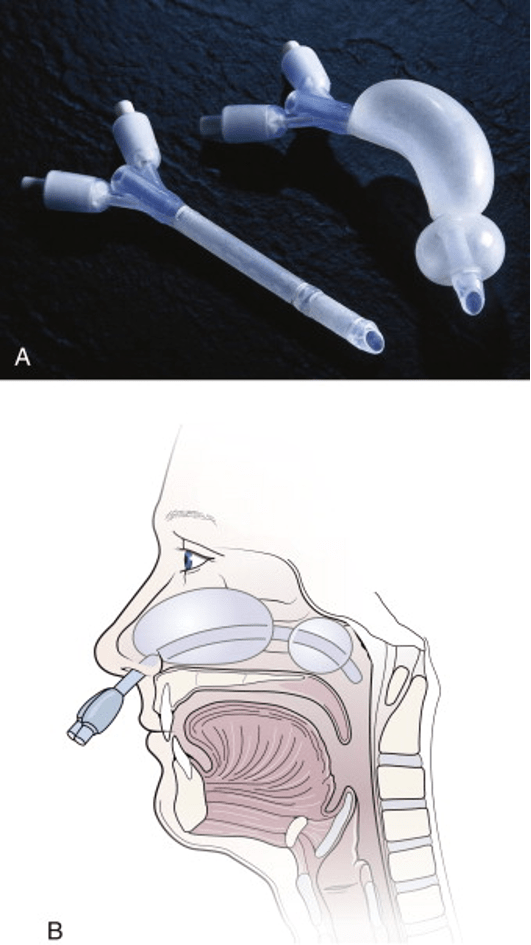

Clinical Significance – this maneuver is performed by vibrating a 512hz tuning fork and placing it on the mastoid process. The patient then informs the provider when they no longer can hear the ringing, at which point the tuning fork is moved in front of the canal. In normal hearing, the patient should still be able to hear the ringing (although it can also occur in sensorineural hearing loss). If conductive hearing loss is present, bone conduction is greater than air conduction.

History – Named after Heinrich Adolf Rinne (1819-1868), a German otologist who received his medical doctorate from the University of Göttingen. He would practice here for the majority of his career exploring the diseases of the ears, nose, and throat. He first described his eponymous test in 1855, but did not get widespread recognition for it until 1881 when it was further publicized by otologists Bezold and Lucae

References

- Firkin BG and Whitwirth JA. Dictionary of Medical Eponyms. 2nd ed. New York, NY; Parthenon Publishing Group. 1996.

- Bartolucci S, Forbis P. Stedman’s Medical Eponyms. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD; LWW. 2005.

- Yee AJ, Pfiffner P. (2012). Medical Eponyms (Version 1.4.2) [Mobile Application Software]. Retrieved http://itunes.apple.com.

- Whonamedit – dictionary of medical eponyms. http://www.whonamedit.com

- Up To Date. www.uptodate.com

- Heck WE. Dr. A. Rinne. Laryngoscope. 1962;72(5):647-652. [link]